Géologie et exploration

Gravity Survey

Dévoiler les secrets de la Terre : Le pouvoir des levés gravimétriques dans l'exploration des hydrocarbures

La recherche de pétrole et de gaz naturel emmène souvent les explorateurs dans les profondeurs de la Terre, où les méthodes traditionnelles sont insuffisantes. Entrez les **levés gravimétriques**, une technique d'exploration puissante qui utilise les variations subtiles du champ gravitationnel de la Terre pour cartographier les structures géologiques cachées.

**Dévoiler l'invisible :**

Les levés gravimétriques reposent sur le principe que les différents types de roches ont des densités différentes. Les roches plus denses, comme celles contenant des hydrocarbures, exercent une force gravitationnelle plus forte. En mesurant méticuleusement l'intensité de la gravité terrestre sur une zone donnée, les géophysiciens peuvent identifier les anomalies - des zones présentant des lectures gravitationnelles inhabituelles.

**Une symphonie de signaux :**

Au cœur d'un levé gravimétrique se trouve un instrument spécialisé appelé **gravimètre**. Ce dispositif sensible mesure les infimes différences de gravité, révélant les paysages cachés sous la surface. Ces mesures sont ensuite traitées et interprétées, créant des cartes détaillées qui dépeignent les structures géologiques sous-jacentes.

**Les signes révélateurs :**

- **Dômes de sel :** Ces structures massives sont souvent associées à des pièges d'hydrocarbures, car elles créent une barrière qui empêche l'échappement du pétrole et du gaz.

- **Bassins :** Dépressions à la surface de la Terre, les bassins sont connus pour accumuler des couches sédimentaires pouvant contenir des hydrocarbures.

- **Failles :** Les cassures de l'écorce terrestre peuvent créer des voies de migration et d'accumulation des hydrocarbures.

**Au-delà de la recherche de pétrole :**

Les levés gravimétriques ne se limitent pas à l'exploration des hydrocarbures. Ils sont également utilisés pour :

- **Cartographier les aquifères souterrains :** La compréhension des schémas d'écoulement des eaux souterraines est cruciale pour la gestion des ressources en eau.

- **Détecter les gisements minéraux :** Les minéraux denses, comme les gisements de minerai, créent des anomalies gravitationnelles distinctives.

- **Étudier les mouvements des plaques tectoniques :** La surveillance des changements de gravité peut aider les scientifiques à comprendre la dynamique de l'écorce terrestre.

**Un outil puissant avec des limitations :**

Si les levés gravimétriques offrent un outil précieux pour comprendre les structures souterraines, ils ont également des limites. Ils sont plus efficaces pour identifier les caractéristiques à grande échelle et peuvent avoir du mal à localiser les structures plus petites. De plus, les anomalies gravitationnelles peuvent être influencées par d'autres facteurs, comme les variations de densité du socle rocheux, ce qui rend l'interprétation difficile.

**Conclusion :**

Les levés gravimétriques sont un outil essentiel dans l'exploration des trésors cachés de la Terre. En révélant les variations subtiles du champ gravitationnel de la Terre, ils offrent des informations sur les structures souterraines qui détiennent la clé du déblocage de ressources précieuses. Au fur et à mesure que la technologie continue d'évoluer, les levés gravimétriques deviennent encore plus puissants, jouant un rôle vital pour guider la recherche d'énergie et de ressources dans un monde confronté à des demandes toujours croissantes.

Test Your Knowledge

Quiz: Unveiling Earth's Secrets: The Power of Gravity Surveys

Instructions: Choose the best answer for each question.

1. What is the primary principle behind gravity surveys in hydrocarbon exploration?

a) Different rock types have different densities. b) The Earth's magnetic field varies across different locations. c) Seismic waves travel at different speeds through different rock types. d) The Earth's gravitational pull is strongest at the poles.

Answer

a) Different rock types have different densities.

2. Which instrument is used to measure the minute differences in gravity during a survey?

a) Magnetometer b) Seismometer c) Gravimeter d) Spectrometer

Answer

c) Gravimeter

3. Which of the following geological structures is NOT typically identified using gravity surveys?

a) Salt domes b) Basins c) Volcanic craters d) Faults

Answer

c) Volcanic craters

4. What is a major limitation of gravity surveys?

a) They cannot detect any structures below the Earth's surface. b) They are too expensive to implement for practical use. c) They are only effective in identifying small-scale structures. d) They are less effective in pinpointing smaller structures compared to large-scale features.

Answer

d) They are less effective in pinpointing smaller structures compared to large-scale features.

5. Besides hydrocarbon exploration, gravity surveys are also used for:

a) Predicting weather patterns. b) Mapping groundwater aquifers. c) Analyzing the composition of stars. d) Studying the behavior of animals.

Answer

b) Mapping groundwater aquifers.

Exercise: Interpreting Gravity Anomalies

Instructions:

You are a geophysicist studying a new area for potential hydrocarbon exploration. The following map shows a simplified gravity anomaly map of the region.

Map:

(Insert a simple image of a map with a few areas of positive and negative gravity anomalies)

Tasks:

- Identify the areas with positive and negative gravity anomalies on the map.

- Explain what each type of anomaly might suggest about the underlying geological structure.

- Propose potential locations for further investigation (e.g., seismic surveys) based on your interpretation of the gravity anomalies.

Exercise Correction:

Exercice Correction

The correction should include: - A description of the positive and negative anomalies identified on the map. - An explanation of the potential geological structures associated with each anomaly type. - Proposed locations for further investigation, justifying the choices based on the gravity data.

Books

- "Gravity and Magnetic Methods" by Telford, Geldart, Sheriff, and Keys (2007): A comprehensive guide to gravity and magnetic methods in geophysical exploration, including detailed chapters on gravity surveys, data acquisition, processing, and interpretation.

- "Exploration Geophysics" by Kearey, Brooks, and Hill (2013): A textbook covering a broad range of geophysical methods, with a section dedicated to gravity surveys and their application in hydrocarbon exploration.

- "Applied Geophysics" by Sheriff (1991): Another classic text covering various geophysical methods, with dedicated chapters on gravity and magnetic surveys.

Articles

- "Gravity Surveys in Hydrocarbon Exploration: A Review" by Khan, Ahmad, and Khan (2017): This review paper discusses the history, principles, and applications of gravity surveys in hydrocarbon exploration.

- "Gravity and Magnetic Methods in Hydrocarbon Exploration" by Talwani (1996): A detailed article that covers the theoretical background, data processing, and interpretation of gravity and magnetic data in hydrocarbon exploration.

- "Gravity Surveys for Oil and Gas Exploration" by Oil and Gas Journal (2013): A practical article that focuses on the use of gravity surveys in oil and gas exploration, including case studies and industry trends.

Online Resources

- Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG): A professional organization for geophysicists, offering resources, publications, and conferences related to gravity surveys and other geophysical methods.

- The American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG): A leading organization for petroleum geologists, with a wealth of resources on hydrocarbon exploration, including articles and case studies on gravity surveys.

- Geophysics.org: An online platform providing comprehensive information on various geophysical methods, including gravity surveys, with interactive tools and learning materials.

Search Tips

- Specific Keywords: Use specific keywords like "gravity survey hydrocarbon exploration," "gravity anomalies oil and gas," "gravimeter applications," and "geophysical methods petroleum."

- Advanced Search Operators: Use quotation marks to search for exact phrases (e.g., "gravity survey techniques"). Utilize "site:" operator to search within specific websites like SEG or AAPG.

- Image Search: Utilize Google Image Search to find visual representations of gravity survey equipment, data processing, and interpretation.

- Scholarly Articles: Use Google Scholar to access peer-reviewed research articles related to gravity surveys in hydrocarbon exploration.

Techniques

Unveiling Earth's Secrets: The Power of Gravity Surveys in Hydrocarbon Exploration

(Image: The provided image should be inserted here in each chapter.)

Chapter 1: Techniques

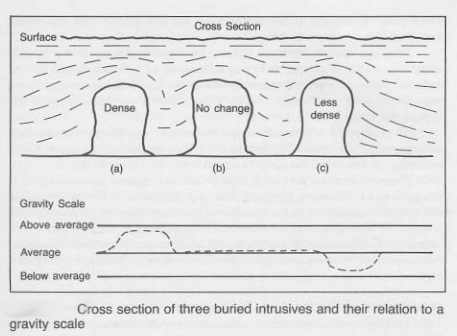

Gravity surveys employ the principle that variations in the Earth's gravitational field are caused by differences in subsurface density. Denser materials, like ore bodies or hydrocarbon reservoirs, exert a stronger gravitational pull than less dense materials. The techniques used to measure these variations are fundamental to the success of a gravity survey.

1.1 Data Acquisition:

The core of a gravity survey is the measurement of the gravitational acceleration (g) at numerous points across the survey area. This is done using a gravimeter, a highly sensitive instrument capable of measuring minute variations in gravity. Different types of gravimeters exist, including:

- Absolute gravimeters: These measure the absolute value of g using techniques like free-fall or rising-and-falling masses. They are highly accurate but less portable and slower than relative gravimeters.

- Relative gravimeters: These measure differences in g between various points. They are more portable and quicker to deploy, making them more commonly used in large-scale surveys. Readings are referenced to a base station with known gravity.

1.2 Field Procedures:

Careful planning and execution are essential for accurate data. Field procedures include:

- Station selection: Stations are strategically positioned to ensure adequate spatial coverage and minimize noise.

- Instrument setup: Gravimeters require careful leveling and stabilization to eliminate errors. Environmental factors like temperature and elevation changes are also meticulously recorded.

- Data logging: Readings are recorded along with metadata including time, location (GPS coordinates), elevation, and environmental conditions.

- Base station monitoring: Regular measurements at a base station provide a reference point to correct for instrument drift.

1.3 Corrections:

Raw gravity data requires several corrections to account for various factors affecting the measurements:

- Latitude correction: Gravity varies with latitude due to the Earth's shape and rotation.

- Elevation correction: Gravity decreases with increasing elevation.

- Bouguer correction: Corrects for the gravitational attraction of the rock mass between the observation point and a reference datum.

- Terrain correction: Accounts for the irregular topography of the survey area, as variations in terrain can significantly affect gravity readings.

- Tidal correction: Corrects for the gravitational influence of the sun and moon.

Chapter 2: Models

Interpreting gravity data involves creating models of the subsurface density distribution. These models aim to explain the observed gravity anomalies.

2.1 Forward Modeling:

This involves creating a theoretical model of the subsurface and calculating the corresponding gravity anomaly. This model is then compared with the observed data. Adjustments to the model (density, geometry) are iteratively made to improve the fit.

2.2 Inverse Modeling:

This approach attempts to directly infer the subsurface density structure from the observed gravity data. It's a more complex process, often involving iterative techniques and regularization methods to constrain the solution and avoid non-uniqueness. Various algorithms are employed, such as:

- Least-squares inversion: Minimizes the difference between observed and calculated gravity anomalies.

- Maximum likelihood estimation: Estimates parameters that maximize the likelihood of observing the given data.

- Bayesian inversion: Incorporates prior information about the subsurface to improve the model's reliability.

2.3 Gravity Anomalies:

Understanding different types of gravity anomalies is crucial for interpretation:

- Regional anomaly: Large-scale variations in gravity related to broad geological structures.

- Residual anomaly: Smaller-scale variations representing local density contrasts, potentially associated with hydrocarbon reservoirs.

- Positive anomaly: Indicates a denser subsurface feature (e.g., salt dome).

- Negative anomaly: Indicates a less dense subsurface feature (e.g., sedimentary basin).

Chapter 3: Software

Specialized software packages are used for processing and interpreting gravity data. These tools automate many tasks, allowing geophysicists to focus on the interpretation of results.

3.1 Data Processing Software:

This software performs corrections, filtering, and gridding of raw gravity data. Examples include:

- GeoSoftware's Oasis Montaj: A comprehensive suite of tools for processing and interpreting geophysical data.

- Petrel (Schlumberger): An integrated reservoir modeling and simulation platform which incorporates gravity data processing.

- Kingdom (IHS Markit): Another powerful platform used in the oil and gas industry.

3.2 Modeling and Inversion Software:

These programs facilitate the creation and testing of subsurface density models. Examples are:

- GM-SYS: A specialized software package for gravity and magnetic modeling and inversion.

- Gravi3D: Software designed for 3D gravity modeling and inversion.

- Many modules within Oasis Montaj, Petrel, and Kingdom.

3.3 Visualization Software:

Effective visualization is crucial for understanding gravity data and models. Common software used for visualization include:

- Surfer: Creates contour maps and 3D visualizations of geophysical data.

- GMT (Generic Mapping Tools): A powerful command-line based package for creating maps and visualizations.

- Visualization tools integrated within the aforementioned processing and modeling software.

Chapter 4: Best Practices

The accuracy and reliability of gravity surveys depend on adherence to best practices throughout the entire workflow.

4.1 Survey Design:

- Appropriate station spacing: Should be determined based on the anticipated size of the targets and the resolution required.

- Careful station selection: Minimize interference from cultural features and terrain variations.

- Redundant measurements: Improve data quality and allow for error detection.

4.2 Data Acquisition:

- Calibration of equipment: Ensure the accuracy and reliability of measurements.

- Meticulous recording of metadata: Essential for accurate processing and interpretation.

- Quality control checks: Regularly verify data quality during the field survey.

4.3 Data Processing:

- Appropriate corrections: Apply all necessary corrections accurately.

- Filtering: Remove noise and highlight significant anomalies.

- Gridding: Create smooth and consistent representations of the gravity field.

4.4 Interpretation:

- Consider multiple models: Avoid reliance on a single model.

- Integrate with other data: Combine gravity data with seismic, magnetic, or well log data for a more comprehensive understanding.

- Uncertainty analysis: Quantify the uncertainty associated with the interpretation.

Chapter 5: Case Studies

Case studies demonstrate the practical applications of gravity surveys in hydrocarbon exploration and other fields. (Note: Specific case studies would need to be added here. The examples below are general illustrations.)

5.1 Case Study 1: Salt Dome Detection:

A gravity survey in a sedimentary basin revealed a strong positive anomaly. Further investigation, using seismic data, confirmed the presence of a salt dome, which was later found to be associated with a significant hydrocarbon reservoir.

5.2 Case Study 2: Basin Mapping:

A regional gravity survey helped define the extent and geometry of a sedimentary basin. The negative gravity anomaly associated with the basin provided valuable information for targeting future exploration drilling.

5.3 Case Study 3: Groundwater Exploration:

Gravity surveys were used to map the extent of a groundwater aquifer. The differences in density between the saturated and unsaturated zones produced measurable gravity variations, aiding in the efficient management of water resources.

5.4 Case Study 4: Mineral Exploration:

A positive gravity anomaly identified a dense ore body. Further investigation with other geophysical and geochemical techniques confirmed the presence of a significant mineral deposit.

(Note: Each case study would require a detailed description including location, methodology, results, and conclusions.)

- Capability Survey Étude de Capacités : Une Dili…

- Gravity (API) Comprendre la densité dans l'…

- cement bond survey Carottage de liaison du cimen…

- Deviation Survey Naviguer sous terre : compren…

- Directional Survey Naviguer dans les profondeurs…

- electric survey Enquêtes Électriques : Éclair…

- Gas Gravity Gravité du Gaz : Un Paramètre…

- Gyroscopic Survey Levée topographique gyroscopi…

- Market Survey Enquêtes de marché : S'orient…

- Check Shot Survey (seismic) Dévoiler les secrets de la Te…

- dipmeter survey Plonger dans les profondeurs …

- Gravity Anomaly Anomalie Gravitationnelle : D…

- Gravity Meter Le Gravimètre : Un Explorateu…

- Gravity Unit (seismic) Unités de Gravité (gu) dans l…

- Pseudogravity (seismic) Pseudogravité : Dévoiler les …

- Gravity Drainage Drainage par gravité : L'aide…

- Gravity Specific Comprendre la densité relativ…

- Gravity flow system Systèmes d'écoulement par gra…

- Oxygen Activation Survey Démasquer les Dangers Cachés:…

- Pre-Award Survey Enquête Pré-attribution : Gar…

- Demande de justification des dépenses Naviguer dans la de… Planification et ordonnancement du projet

- Coût budgété du travail planifié Comprendre le Coût … Estimation et contrôle des coûts

- Les limites de batterie Comprendre les limi… Termes techniques généraux

- Outil DV Outil DV : Un éléme… Forage et complétion de puits

- SOMMAIRE TOC : Comprendre le… Termes techniques généraux

Comments